Regional Experience of Cemiplimab, in Locally advanced and stage IV Head and Neck Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Purpose/Objective

Cemiplimab has been approved for use in England for locally advanced, unresectable and metastatic cutaneous SCC (Squamous Cell Carcinoma). These cancers are usually morbid, have a detrimental impact on patient and carer quality of life and affect older adults, with limited treatment options. The aim of this study is to present a real world experience of the use, toxicity profile, and response rates of Cemiplimab.

Material/Methods

In this retrospective review, we present our regional experience of Cemiplimab (350 mg IV 3 weekly) in locally advanced and metastatic SCC, arising in the head and neck area. The electronic records of all patients who were exposed to at least one cycle of Cemiplimab were reviewed. Data was collected including comorbidities (ACE-27), performance status, and toxicity as well as response rates and overall survival.

Results

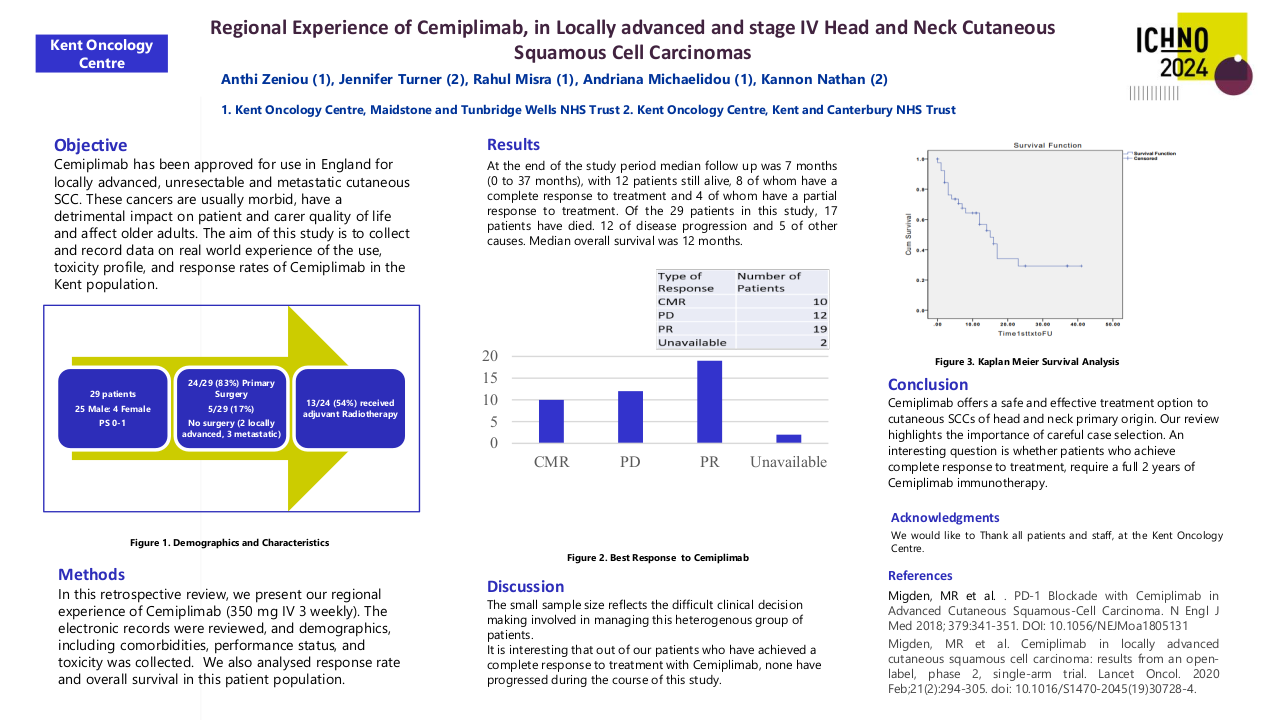

Our patient cohort includes 29 patients, treated between September 2019 and July 2023. Median Age was 76.5 years and 25 of the patients were male with 4 female patients. The median ACE-27 score was 2. All patients had a performance status of 0 or 1.

The majority of patients had locally advanced disease 86% (25/29). Of our patient cohort, 83% (24/29) patients had undergone primary surgery following diagnosis of head and neck cutaneous SCC, with 54% (13/24) patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy following surgery with doses of either 55Gy in 20# over 4 weeks or 60-66Gy in 30-33# over 6 to 6.5 weeks. Of the patients who failed following surgery and/or adjuvant radiotherapy, the mode of failure was locoregional in 79% (19/24). Median Time to failure from primary diagnosis was 6 months.

Of the five patients who did not undergo surgery at diagnosis, 2 had locally advanced disease and 3 had metastatic disease. 3 of these 5 patients had palliative radiotherapy (20Gy/5#) after starting Cemiplimab and 1 of these patients received 20Gy/5# before starting Cemiplimab.

When patients commenced Cemiplimab, response was assessed either clinically, via CT, PET-CT and/ or MRI. The median number of cycles of Cemiplimab delivered was 7. The commonest side effects reported were fatigue (6 out of 29, 21%) and development of a new rash (5 out of 29, 17%). Only 3 of the 29 (10%) patients developed Grade 3 toxicity. All three patients discontinued treatment, one had developed hepatitis, the second patient developed pyoderma gangrenosum and it was unclear whether this was a direct toxicity from Cemiplimab, the 3rd patient developed colitis. All three required steroids and only 1 required hospitalisation. There were no toxicity associated deaths. Of the 3 patients who developed grade 3 toxicity, 2 have died of other causes and one is alive and disease free.

The median time to the first radiological response assessment was 9.9 weeks. The response rate to treatment at first response assessment was 69% (20/29) and overall response rate at the end of the study period was 52% (15/29). Of the 3 patients who had complete response at first assessment this was maintained through the study period, and of the 17 patients who had a partial response at first assessment, 6 patients went on to develop complete response. All 9 patients who achieved complete response were able to maintain this throughout the study period.

At the end of the study period median follow up was 7 months (0 to 37 months), with 12 patients still alive, 8 of whom have a complete response to treatment and 4 of whom have a partial response to treatment. Of the 29 patients in this study, 17 patients have died. 12 of disease progression and 5 of other causes. Median overall survival was 12 months.

We note that our study population was overwhelmingly male, however in terms of demographics and toxicity profile was reflective of the populations presented in clinical trials. The small sample size reflects the difficult clinical decision making involved in managing this heterogenous group of patients.

It is interesting that out of our patients who have achieved a complete response to treatment with Cemiplimab, none have progressed during the course of this study.

Conclusion

Cemiplimab offers a safe and effective treatment option to locally advanced unresectable or metastatic cutaneous SCCs of head and neck primary origin, which overwhelmingly affect older adults. Our review highlights the importance of careful case selection. An interesting question is whether patients who achieve complete response to treatment, require a full 2 years of Cemiplimab immunotherapy.

1. Migden, MR et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:341-351. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131 2. Migden, MR et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Feb;21(2):294-305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30728-4. 3. Baggi A, et al. Real world data of cemiplimab in locally advanced and metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Nov:157:250-258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.018.