Do all roads lead to Speech and Language Therapy? Evaluation of a pilot waiting-list initiative for radiation-oncology head and neck cancer patients to enhance access to Speech and Language Therapy

Purpose/Objective

All head and neck cancer (HNC) patients receiving radiotherapy should have access to Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) for management of speech and swallowing(1).

A pilot SLT education group programme, was delivered over a 10-week-period in a radiation-oncology (RO) service in 2023 as part of a waiting-list initiative. The purpose was to increase timely access to SLT for HNC patients.

We aimed to evaluate the SLT pilot education group and make recommendations for future service delivery models.

Material/Methods

HNC patients receiving radical radiotherapy (n=22) prioritised as low-risk SLT patients, attending for RO, were identified and invited to attend an SLT education session. High-risk patients requiring intensive SLT intervention e.g. hypo-pharyngeal cancer, advanced laryngeal cancer and T4 tumours were excluded.

Topics covered included an introduction to eating, drinking and swallow (ED&S) mechanisms, side-effects of radiotherapy and potential impact on ED&S, management strategies and prophylactic swallowing exercises. Sessions were interactive and patient information leaflets were provided. Invitations to attend additional sessions were extended; individual appointments were available on patient request.

Swallowing outcomes (The MDADI global score, EAT-10) and patient satisfaction levels were completed at the time of attendance.

Data was collected on patient demographics, treatment plans, attendance rates, admissions, patient self-report of dysphagia and impact on quality of life. Waiting-list times and cost savings were calculated.

Results

The results demonstrated that 14 patients attended (64%) the offered education session (9 males; mean age 66.5, range 46-84 years)

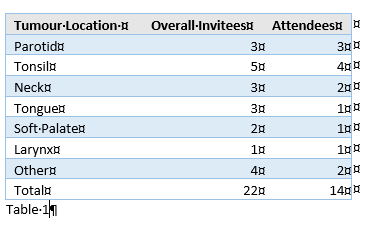

The majority of patients had disease staging as ≤T2 (57%; 8/14). Attendees were heterogeneous with regard to tumour location (Table 1).

No patients requested individual appointments.

Of 14 attendees, 5 required inpatient admission (36%), compared to 6 (75%) patients who were invited and did-not-attend the education session.

Reason for admission analysis revealed all 5 attendees required admission for symptom control, chiefly pain management, nausea, constipation and weight loss. Requirement for NG feeding was stated in 3/5 (60%) cases. Inpatient NG insertion requirement in the non-attender cohort was 67% (4/6).

Treatment for pneumonia was required in 0% of cases.

Attendees were admitted later into their treatment (mean fraction at time of admission 32; range 28-35) when compared to non-attendees (mean fraction at time of admission 23.5; range 13-35).

The presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia as per self-report was identified in 8 (57%; EAT-10 score ≥3) attendees. However, the majority of attendees did not consider dysphagia as affecting quality-of-life (Mean MDADI global-question score of 3).

All attendees reported the education session as helpful, they planned to implement advice given and would recommend attendance to fellow-patients.

Seven patients received SLT input within local departmental standards (KPI of by 5 fractions). An additional 7 patients accessed SLT who would not have been seen due to service constraints. A further 8 patients would have received SLT guidance if they had attended the education session offered.

When comparing costings for individual versus group interventions, a saving of €482.46 could be made per group programme for a similar patient cohort(2).

Conclusion

This waiting-list group initiative provided access to SLT for a cohort of low-risk HNC patients who would not have received guidance due to departmental service constraints.

This pilot study has shown that group interventions can be an effective way to introduce the role of SLT, deliver general patient education and introduce swallowing rehabilitation to this specific client group.

Preliminary findings suggest that this pilot waiting-list initiative was an effective medium to enhance patient experience and encourage patient autonomy and empowerment for HNC patients during their radiation-oncology journey.

However, this pilot programme was delivered to a low-risk HNC patient cohort and a similar approach may not be appropriate for HNC patients with more extensive disease where an individualised treatment programme is the gold-standard (3).

Group intervention can be a necessary solution to address service delivery demands in the existence of resource constraints. Nevertheless, the value, impact and effectiveness of tailored face-to-face SLT interventions with HNC patients who present with acute, chronic and complex ED&S needs cannot be underestimated(4, 5).

This initiative will continue and facilitate further analysis regarding admission avoidance, alternative feeding requirement and swallow function outcomes. Further analysis exploring rationale for non-attendance will assist with future programme design.

Data will also be used to assist with future service development, resource allocation and staff planning.

1 Baijens, L. W. et al (2021) European white paper: oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06507-52 HIQA (2018) Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies, Dublin3 Clarke, P. et al (2016) Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 130, S176-S1804 Patterson J, Wilson JA. The clinical value of dysphagia preassessment in the management of head and neck cancer patients.Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;19:177–81. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e328345aeb0.5 Govender, R. et al (2019) Helping Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Understand Dysphagia: Exploring the Use of Video-Animation.American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology Vol 28 697-705